Article 4 GDPR (1): Personal data

(2016)

‘personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’); an identifiable natural person is one who can be identified, directly or indirectly, in particular by reference to an identifier such as a name, an identification number, location data, an online identifier or to one or more factors specific to the physical, physiological, genetic, mental, economic, cultural or social identity of that natural person;Personal data is data that can be traced to a real, natural person. Just like Food On Route, there are tens of thousands of user-friendly apps and smart artefacts that store and share personal data. This data is used to personalize these services in such a way, that they meet our individual needs and expectations. At first glance, this may all seem very convenient, but the interfaces of these artefacts and services are not designed to make their users aware of the risks they run when their personal data is processed. In many cases, this data will be sold on, requested by governmental agencies or unintentionally leaked through mistakes or hacks. This means personal data can end up in contexts where it could be of harm to the people it is connected to. In most cases, this is not a thing an interface designer primarily aims at when designing user-friendly interfaces. When designing interfaces, the main goal is to help humans operate complex technology and find their way through large amounts of information. Whether it is browsing the contents of Wikipedia, or using GPS Navigation in a car, the role of the interface is to make this complex technology easy enough to use for an average human being.

In 70 years, computers have become increasingly cheaper, smaller, more powerful and easier to use. They are all around us and life as we know it, would not be possible because of easy-to-use networked information technology. The reason this technology is so easy-to-use now? Well designed user-friendly user interfaces.

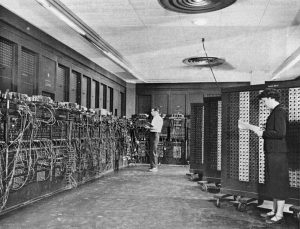

Computers have become incredibly small and powerful in a relatively short amount of time. On February 14th 1946, the ENIAC, the first electronic Turing Complete computer, was presented to the public. Although expensive and complicated –it had to be operated by six people using switchboards and punch cards– its birth marked the start of the era of information technology. Wikipedia: Moore’s Law

(1965)

Moore's law is the observation that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years. Although Moore’s law no longer is an accurate benchmark for the steady pace of increasing processor power, the last seven decades computers have become more powerful, smaller, cheaper and most importantly: very easy to use.

The ENIAC, 1946. Source: Wikipedia.com

Measured in raw computing power, Super computer Smartphone

(2017)

According to Huawei, their 2017 NPU mobile processor is capable of 1,92 TFLOPS, While the ASCI Red Super Computer hit 1,03 TFLOPS in 1996.current smartphones already outperform supercomputers from the early 1990’s. According to the mobile survey by Ericsson, there are around 7.5 billion of them around the world. Ericsson predicts 20 billion devices to be connected to the internet by 2030. This may be smart watches like the Apple Watch, but fridges; cars and even toilet roll-mounts as well. Although it will take some time before every household appliance will have an internal computer and network connection, we already can see an ever increasing amount of networked smart artefacts in our daily lives. This phenomenon is often referred to as ‘the Internet of Things” (IoT): smart televisions with internet connection, gps and heart rate sensors in smart watches, autonomous cars and refrigerators that monitor their content. More often than not, to operate them these networked artefacts will give very little cues in the sense of actual interfaces. We can operate them by just being in the same room or by talking to them: Amazon’s Alexa or Google’s Nest both do with sensory and audio input.

Another indication of information technology becoming an integral part of human life, society and culture around the world was the mid-2017 announcement by Facebook that it had reached two billion monthly users. That same month, Google announced that there were two billion active Android devices, making Android effectively the largest operating system in the world. Life as we know it, would be completely different without this readily available, cheap, global computer network of interconnected things and humans. A network that generates a staggering amount of data, too: IBM STUDY

(2011)

Every day we create 2.5 quintillion bytes of data – so much that 90 percent of the world’s data today has been created in the last two years alone. In 2011, IBM estimated that 90% of the worlds data today had been produced in the last two years alone. This data is increasingly being produced by devices that have little or no direct conscious human input: scanners around highways scan and record the license plates of passing cars, WiFi- and Bluetooth-beacons monitor and plot the behaviour and movement of customers in and around shops. Not to mention the millions of cameras, be it for security surveillance or advertisement monitoring and personalization, that record millions of hours of human behaviour around the world.

The Graphical User Interface of a XeroX STAR – Computer.

These enormous amounts devices that gather enormous amounts of data would not so easily have surrounded us, if it were not for easy-to-use user interfaces. Ever since the conception of the first practical Graphical User Interfaces (GUI), in the early 1980’s by and Tim Mott Designing Interactions

(Moggridge B.J., 2007)

(Moggridge, 2007), computers have become increasingly easy-to-use and the interaction became more intuitive with every iteration of a product. Right now, we have touch screen interfaces, Voice User Interfaces (VUI), (the ones like Apple’s SIRI or Amazon’s Alexa) and a wide range of sensory interfaces such as Microsoft’s Kinect, and Garmin’s sports-devices with heart rate and GPS sensors. Apple offers a biometric scanner now, to unlock your iPhone X by scanning the 3D profile of your face. Just holding up the phone in front of your face is enough to start using it.

Purely compared by computing power, an Apple Watch is roughly 3,2 million times more powerful than the 1946 ENIAC.

Without these user interfaces, most humans would never be able to interact with computers the way they do now. Whether it is booking a flight or sending a Tweet; in 70 years, operating computers has evolved from a complicated task only suited for scientists and engineers into a pleasant experience almost anyone can have.

Good product design is all about lowering friction between the product an the human that uses it.

As an interface and user experience designer, I have not known better than that optimizing for usability was paramount. Any product that left the shop, had to be user-friendly; be it an app, a touch screen interface or a website. Another way of looking at a user-friendly interface is that it is a low friction interface. In 1955, , a renowned product designer, described what he believed to be the core of proper product design in his book Designing for the People

(Dreyfuss H, 1955)

New York: Allworth Press‘Designing for the People’:

“We bear in mind that the object being worked on is going to be ridden in, sat upon, looked at, talked into, activated, operated, or in some other way used by people individually or en masse. When the point of contact between the product and the people becomes a point of friction, then the industrial designer has failed. On the other hand if people are made safer, more comfortable, more eager to purchase, more efficient – or just plain happier -by contact with the product, then the designer has succeeded.”

(Dreyfuss, 1955)

Dreyfuss claims that people need to be happy and comfortable while using a product. If the product is hard to use, if it takes too much time and cognitive power or makes them feel unsafe, people will grow wary, irritated, scared, or bored. Subsequently, chances are they will stop using the product altogether and advise their friends and family against buying it. Whether it is a vacuum cleaner, a television, a car or a toothbrush, a product should not demand too much effort in using and the use should lead to a positive experience. Since smart artefacts and services qualify as consumer products, the same paradigm should apply here. Using a smart artefact should be easy, it should provide a pleasant experience, and provide that ease-of-use, the interface should be easy to use.

Left: Honeywell Thermostat, designed by Henry Dreyfuss. Right: NEST Smart Thermostat

In 1988, Mark Weiser shared the concepts of ‘Ubiquitous Computing’ and ‘Calm Technology’. His idea was that in the future, computers would be everywhere around us and human interaction with computers was to be to be unconscious and had to create calm.

also envisioned that interacting with computers should be as frictionless as possible. Weiser, Chief Technologist at XeroX PARC (the company where the first Graphical User Interface (GUI) that became available to a large audience was developed), correctly predicted that artefacts like smartphones and PARC Pad

(1990)

In 1996 there PARC developed concept known as the PARC Pad, a hand held computer with a stylus.tablets would become an integral part of human lives and he foresaw the rise of social media and voice-based computer interfaces. In one of his publications, Weiser merged many of these concepts into what he called Ubiquitous Computing (Weiser, 1988). In the future, he predicted, computers would be everywhere to help us with our daily chores. He believed that “The more you can do by intuition the smarter you are; the computer should extend your unconscious.” (Weiser, 1996)

Weiser predicted that computers would become ‘invisible servants’, that they could be operated in an unconscious way and that they would be omnipresent. (Weiser, 1996) Computers would no longer be separate devices we would have to consciously interact with; in stead they would “be embedded in walls, chairs, clothing, light switches, cars – in everything.”

He saw Ubiquitous Computing as the ‘Third Wave in Computing’ the first being mainframes (like the ENIAC) and the second being personal computers, like desktop and laptop computers. He foresaw the rapid growth of internet usage and the fact that microprocessors were already present in many consumer products such as alarm clocks and phones, THE COMING AGE OF CALM TECHNOLOGY[1]

(Weiser M, Brown J.S., 1996)

"The important waves of technological change are those that fundamentally alter the place of technology in our lives. What matters is not technology itself, but its relationship to us."effectively predicting the Internet of Things (IoT) as we know it now.

To describe his ideas about how we would have to interact with these omnipresent computers, he coined the term ‘Calm Technology’. According to Weiser this was ‘technology that moves from the periphery of our attention and back’ (Weiser, 1996). In other words, technology should only present itself when needed. Computers should merge into the background and only demand attention if necessary, much like the push-notifications on our smartphones. Most importantly, the computers should help their users in such an invisible way, Ubiquitous Computing

(Weiser M, 1993)

Long-term the PC and workstation will wither because computing access will be everywhere: in the walls, on wrists, and in "scrap computers" (like scrap paper) lying about to be grabbed as needed. This is called "ubiquitous computing", or "ubicomp".‘the ubiquitous computer leaves you feeling as though you did it yourself.’

Don Norman thinks that great designers create great experiences. Interacting with technology should not be a subconscious activity that results in a good experience. Alan Cooper claims that the design of interactive products should focus on the goal a user wants to achieve, not on the interaction or the product itself.

It is this direct and positive, personal experience as a result of low-friction interaction that has become a main goal of interface design. , former designer at Apple and co-founder of the Norman Nielsen Group –to some the ‘godfather of User Experience design’– , elaborates in The Design of Everyday Things

(Norman D, 2013)

“The design of everyday things” on this happiness. “Great designers produce pleasurable experiences” (Norman, 2013) ‘Experience is critical’ he says. Because ‘it determines how fondly people remember their interactions’. (Norman, 2013) It is not so much about the actual use of a device, but the resulting positive experience that determines the eventual success of an interaction. In his book, Norman explains that this ‘experience’ of an interaction with a product takes largely place in the subconscious level. Most human behaviour, he explains, is based upon subconscious processes. (Norman 2013:44) “We are good at it”, he continues: “Sub-conscious thought matches patterns, finding the best possible match of one’s past experience to the current one. It proceeds rapidly and automatically, without effort.”

Norman discerns three levels of processing in his Approximate model of Human Emotion and Cognition: Reflective, Behavioural and Visceral (Norman 2013:50), where only the Reflective level is a truly conscious level. It is ‘cognitive, deep and slow’ and best to be used for learning and evaluation. The visceral level is where ‘the reptile brain resides’. This is the place for desire, fear, disgust, anger. Our primal reactions come from the visceral level and on this level we are mainly triggered by first appearance. This is the level where visual design cues – colours, shapes, call-to-actions – are processed. The behavioural level however, is ‘home to interaction’, he states. (idem: 54) This is the level of processing, Norman states, where we use our learned and automated skills. We do not need to have attention to detail because we ‘know’ how we need to do things. Tie our laces, opening a door, browsing a website, we act without really thinking. We simply ‘know’ how it is done right. Norman stresses that all levels of processing are important for the designer to create true delight, but when it comes to designing good looking, low-friction interactions, the visceral and behavioural level is where the focus lies.

“If we design and develop digital products in such a way that the people who use them can easily achieve their goals, they will be satisfied, effective, and happy.”

About Face 4

(A Cooper, Reimann R, Cronin D, Noessel C, 2014)

Indianapolis: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.(Cooper, 2014:33)

, the ‘Godfather of Visual Basic’ and inventor of the concept of Persona’s, observes that when designing interfaces for software, we need to focus on the goal an end user aims to achieve. Someone who uses a computer, does not want to use that software or hardware as such. He aims at achieving a certain goal with that computer. He taps into Norman’s reasoning by focusing on the result a user wants to get instead of the interaction with smart artefact or service, in line with what Mark Weiser said about Ubiquitous Computing he states:

Designing for minimal cognitive load has been the goal for many years amongst interaction designers. Even exploiting human flaws like laziness and sensitivity to addiction have proved to be very successful interaction strategies.

Following this principle of low cognitive load, Steve Krug wrote the now famous book on web design, titled Don’t Make me Think

(Krug S., 2006)

(2nd edition). Berkeley, California: New Riders“Don’t make me think”. (Krug, 2000) Steve Krug too advises to design and build interactive interfaces in such a way, that navigating the interface becomes an intuitive task instead of a cognitive one. A good web page should be ‘self-evident. Obvious. Self-explanatory.’ .

Krug’s book provides principles and patterns that aim towards users ‘scanning’ pages instead of ‘reading’ them in detail.(Krug 2006:22). He advises to set up pages and menus to make ‘mindless choices’ instead of well-thought decisions. Because users prefer to ‘muddle through’ interfaces instead of ‘figuring things out’. Actually, Krug advises designers to intentionally design websites optimized towards the subconscious and even sloppy behaviour of humans to make them more user-friendly.

To design for the subconscious user and using human traits as an agent to achieve better interaction is one thing, but there are also models that focus on persuading and nudging people into doing things they would probably would not do when given room for conscious thought. , a behavioural designer whose work and working theories have become the basis of many successful online concepts, begins with stating that ‘we are fundamentally lazy’. His A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design

(Fogg B.J., 2009)

Behavioural model of persuasive design (Fogg, 2009) uses this laziness as a de facto design pattern:

“(…) persuasive design relies heavily on the power of simplicity. A common example is the 1-click shopping at Amazon. Because it’s easy to buy things, people buy more. Simplicity changes behaviors.”

A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design

(Fogg B.J., 2009)

(Fogg, 2000)

To take this another step further, as describes in his book “Hooked”, the success of a smart artefact or service, largely depends on whether or not people form some sort of an addiction while using them. To Eyal, addiction is the highest form of user loyalty.

“In order to win the loyalty of their users and create a product that’s regularly used, companies must learn not only what compels users to click but also what makes them tick” Hooked

(Eyal N, , 2014)

A 2011 university study suggested people check their phones thirty-four times per day. However, industry insiders believe that number is closer to an astounding 150 daily sessions. Face it: We're hooked. (Eyal, 2014)

This strategy works quite well, Examination of neural systems sub-serving facebook “addiction”.

(Bechara A, Xue G, Turel O, Xiao L, He Q, 2014)

Because addictive behaviors typically result from violated homeostasis of the impulsive (amygdala-striatal) and inhibitory (prefrontal cortex) brain systems, this study examined whether these systems sub-serve a specific case of technology-related addiction, namely Facebook "addiction."research on the subject says.

The pattern we need to observe here: the design for a successful smart artefact or service is aimed at keeping human interaction on a subconscious level at most times. As per Weiser’s idea of ‘Calm Technology’, we do not want to have the artefact ‘get in the way’ of the goals that user aims to achieve. A successful interface is the one that adapts to the user’s sub-conscious and visceral behaviour and where interaction results in a pleasant experience, if that user’s goal will be achieved. However, these design strategies can also be used to take advantage of human flaws in order to make customers spend more money than they intended and even to make them dependent of your smart artefact.

A poignant example is for this is provided by ride-hailing service Uber. Through its app, Uber was able monitor the battery status of a smartphone. Behavioural scientists at Uber predicted people would agree to pay a higher ride price when their battery was about to die. Uber has denied putting this knowledge into practice, This Is Your Brain On Uber

(2016)

but it shows how people’s behaviour could easily be manipulated.

The majority of large technology companies have exploited easy-to-use design strategies to extract as much data from their users as possible in order to monetize their user base. Even though this is questionable and sometimes outright dishonest, it is a very profitable strategy.

User-friendly design seems to have evolved from a well-intended way of offering information, clarification and means of control for inexperienced computer users into a way of nudging, even manipulating people into behaviour that is not necessarily in their best interest. uses the term ‘Surveillance Capitalism’ for business strategies that depend on extracting as much personal data as possible from users, in order to make money on that data. She sketches a rather dystopian image of large technology companies that use easy-to-use artefacts and services to generate as personal much data on their frequent users as possible. Google, Facebook, Amazon, Uber, but a lot of smaller companies as well, know this data is a gold mine: if you know enough about someone, you can let them do anything you want. The secrets of Surveillance Capitalism

(Zuboff S, 2016)

She quotes a Silicon Valley data scientist:

“The goal of everything we do is to change people’s actual behavior at scale. When people use our app, we can capture their behaviors, identify good and bad behaviors, and develop ways to reward the good and punish the bad. We can test how actionable our cues are for them and how profitable for us”

As most of us use these smart artefacts on a daily, even virtual constant basis, it becomes hard to keep track of how much personal data we are sharing. You might come to know this if you would spell out the privacy policies and terms & conditions of these companies, but these are made hard to read or understand, Apart from that, even if you agree with the way a company treats your data, this all can rapidly change if the company is bought by someone else. For example in 2014, Facebook bought the instant messaging service Whatsapp for the staggering amount of $16 billion. The sole reason was its user base: Facebook first promised not to link the two services in terms of data, WhatsApp to share user data with Facebook for ad targeting — here’s how to opt out.

(2016)

Techcrunchbut that was a promise they did not keep.

This lack of corporate honesty trickles down in the design of interfaces as well. Facebook promises to safeguard your privacy by offering a Basic Privacy Settings & Tools | Facebook Help Center | Facebook.

(2018)

plethora of settings to ensure the right people see only see the things you want them to see on your timeline and profile. However, even if you would shield your profile and timeline for just about everyone, Facebook still ‘sees’ everything and will use that data as it likes. A quick glance at the privacy settings in your iPhone shows that many (often free) apps like Shazam request access to the camera, microphone photo album and GPS-data. This access is sometimes not necessary for the app to function properly, but the reason this access is requested, is because some companies use these functionality That Game on Your Phone May Be Tracking What You’re Watching on TV.

(2017)

New York Times, Maheshwari, S.to eavesdrop on the owner’s smartphone in order to better target their advertising.

By surrendering so much data to so much technology companies, users of smart artefacts and services risk their privacy. This can have serious consequences.

These large amounts of acquired data enable companies like Google and Facebook to build detailed profiles on real people, –possibly on any of us– even if you have not used social media for a while. Although many people have warned about the risks of this context-rich profiling, the dangers in terms of privacy are greater than ever. Through trackers and online beacons, email-tracking, even through analysis of the GPS data on our pictures and cell phone locations, these profiles can get quite detailed. It may be soon that 3D face profiles, generated through Apple’s iPhones X will be stored and sold as part of personalized profiles as well. In the end, it is all in the interest of companies like Facebook and other data brokers that depend on Get your loved ones off Facebook

(Virani S, 2013)

detailed profiling of humans around the world. This also means that through the available data, many of the different social contexts each individual is part of (work, friends, sports, public life) are likely to merge one way or the other. This is why Helen Nissenbaum refers to privacy as :

Developed by social theorists, it involves a far more complex domain of social spheres (fields, domains, contexts) than the one that typically grounds privacy theories, namely, the dichotomous spheres of public and private.

( , 2002)

Humans tend to create different spheres of context in their lives, where they can behave accordingly. The sphere of context of a family life is different than that of the sphere of context of a working life, and again different from the sphere of context between close friends. These different spheres of context tend to merge when data brokers and tech companies merge all collected data on one individual into one data set.

Even more, a smartphone alone can damage contextual integrity by itself. A smartphone merges several devices –camera, internet browser, address book– into one artefact. Through their network connections, we can backup these phones on servers elsewhere. It would be very inconvenient if private messages would end up with the wrong recipients or that private pictures would end up on the public internet, but the celebrity Gang of hackers behind nude celebrity photo leak routinely attacked iCloud

(Arthur C, Topping A, 2014)

Apple iCloud hack in 2015[ref] proved this can happen.

Jessica Vitak describes this phenomenon as [ref id='569']‘Context Collapse’.

A well known and gruesome example is a series of suicides directly connected to the Ashley Madison was a site that offered a discrete way to engage in an affair. The site proved to be less safe and discrete than promised and the data was eventually leaked by hackers who at first demanded a ransom. The context of a site aimed at secret affairs, suddenly collapsed onto a public context. For a few affected individuals, this proved to be too much to handle.o privacy is not just about ‘having things to hide’. Privacy is all about being able to see and control where personal, intimate information ends up and to ensure this data will be of no harm to you. We can conclude that the way many tech companies collect personal data of their user now, is not doing a great job in terms of contextual integrity. Even more, as we can conclude from the interface design strategies as mentioned above, the interfaces of their services are not being clear, nor honest about this.

Apart from technology companies, governments also profit from these large amounts of data. As the PRISM-disclosure25 proved, governments – especially the US government–, make sure that in the name of national security, personal data collected via social networks and other sources, end up on the servers of secret agencies like the NSA. , a well know technology sceptic, warned us in 2009 that the way the internet was used, would aid totalitarian regimes in providing detailed information on the behaviour and opinion of How the Net aids dictatorships

(Y. Morozov, 2009)

just about any citizen. It would enable politicians to influence public opinion, elections and would enable them to weed out opposition and critics. With the What Did Cambridge Analytica Really Do for Trump’s Campaign?

(Lapowski I, 2017)

News that Cambridge Analytica CEO Alexander Nix approached Wikileaks founder Julian Assange last year to exploit Hillary Clinton’s private emails has amplified questions about Cambridge's role in President Trump's 2016 campaign.Cambridge Analytica-aided election of Donald Trump and the Brexit-referendum we can acknowledge his observations were not far from the truth at all.

Current developments in the People’s Repuplic of China show what it will be like when governments can implement monitoring systems virtually unopposed. Powered by E-commerce platform Alibaba, Sesame Credit provides a personal record on about any Chinese civilian, where credit rating, behaviour and social network will put a rating to an individual’s trustworthiness, de facto making the state declare who is and who is not to be trusted. This in turn may even result in China to bar people with bad ‘social credit’ from planes, trains.

(2018)

getting banned from planes, purely based upon their social credit status. As China has one of the most dense surveillance infrastructures, with China’s CCTV surveillance network took just 7 minutes to capture BBC reporter.

(Russell J, 2017)

powerful facial recognition and image processing, it will be a matter of time before these two are thoroughly linked up. By then, it will be very hard to make individual choices without constantly assessing the possible consequences it may have for your social credit status.

Although easy-to-use interfaces are necessary to operate the smart artefacts and services we have surrounded ourselves with, there is a dilemma: easy-to-use interfaces generate little awareness on privacy risks. To what extend should we keep focusing on ease of use?

If we use Don Norman’s, Alan Cooper’s, even Dreyfuss’ perspective, sound product design and good interface design in particular, helps a human achieve a goal as efficiently and frictionless as possible. The goal this human aims to achieve should be the focus of the design process, the operation or interaction with the artefact itself, not so much. But by providing people with easy-to-use, low-friction user interfaces that in turn control networked smart artefacts and services, a moral dilemma has popped up. For an average human being, it becomes very hard to oversee what personal data is being shared and what consequences they may have on the long run. Because the interaction with smart artefacts and services is designed to require as little cognitive load as possible – be it only in terms of usability or with a more sinister agenda– there is mostly little awareness on the part of the average end user.

Here lies the dilemma of the interface designer. By reducing friction through user interface designs that are so user-friendly people mostly do not even notice them anymore, interface designers intentionally reduce cognitive involvement of their users. By ‘not making them think’, they are making people too dependent on technology. By providing these user-friendly interfaces, they are making their public willingly –or un even worse: unwillingly– vulnerable to the agendas of large companies and government agencies but for mistakes, unintended leaks and hacks as well. With that, we indirectly are putting their privacy at stake.

It needs to be stressed that by no means I consider the core principles of Cooper, Norman, Krug and Weiser flawed. The main focus of their work is and has been making the computer a more pleasant and less stressful tool to work with and that ideal remains valid. I strongly believe that they have always reasoned from a human centered, idealistic point of view and that they now would strongly disapprove the current state of affairs when it comes to the concept of surveillance capitalism. In the end, computers should remain easy-to-use, but the question here is, to what extent and how can we make them more trustworthy when it comes to a user’s contextual integrity?