In 2016, together with a group of students I developed an app that enabled users to geolocate roadside booths where home-grown and home-made groceries were sold. We found out we had overseen an important thing.

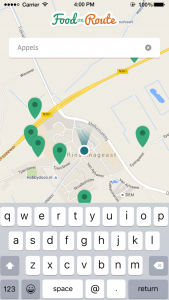

Early 2016, a few students I teamed up with, were finalizing a smartphone app for which I had developed the concept. The app would enable people in the northern part of the Netherlands to locate roadside vendors of home-made and home-grown groceries on a map and plot a cycling route between different roadside vendor booths. As an extra service, meal recipes could be uploaded to the app’s website, which in turn were translated into a cycling route using the ingredients and the corresponding vendor booths. This app would make the task of shopping for groceries a more engaging and fun experience than the daily drive to the mall. We christened the app ‘Food on Route’.

Road Side Vendor Booth

Splash Screen & Search Results | Food on Route

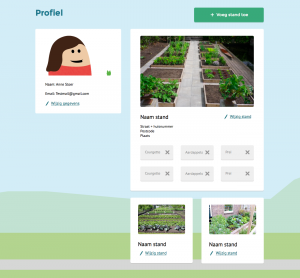

Profile Page | Food on Route

The app enabled cyclists to take pictures of road side vendor booths, and plot them onto a map using the GPS metadata. These cyclists then could fill out a form submitting information on the groceries that were available at that certain booth. Local vendors were able to ‘claim’ their booth on the website, in order to complete a detailed online profile of their booth. We had a working, good-looking prototype and where it was showcased, it was received well.

However, it appeared we had overlooked an important thing.

It turned out the app could also be used by the Dutch tax authority to pinpoint these roadside vendors, who in turn would run the risk of having to pay fines and extra taxes.

Upon finalizing the app, it turned out we had missed to see an important and unwanted ‘by-product’ of this service. We unintentionally had designed an app that could enable the Dutch Tax Authority to locate vendors and to check if they were required to charge VAT. If so, the owner of a booth may needed to pay extra taxes because of the income they would have generated from selling groceries. As the Dutch Tax law states, any individual that offers goods or services while creating publicity around that offering, is considered to be running a business and is therefore obliged to report and pay VAT.

User research had shown that most vendors just sold their surplus groceries and would not make a lot of money on it. Neither had they the intention of starting and maintaining a business. If the Tax Authority would sign up with our service and pinpoint the vendors’ location, it would be able to see who was living at that address and require the individual grocery seller to report and pay VAT.

This would at least provide these vendors with a lot of extra paperwork and would probably discourage them from selling their groceries via roadside booths altogether. By enabling other smartphone users to provide location based data on these vendors, we had unintentionally put these vendors in a vulnerable position. In the end, it was their choice to charge or not to charge VAT, but we had indirectly enabled the Dutch tax authority to easily check out anyone whose address was geolocated near a roadside vendor booth.

We had created an easy-to-use service that could gather a lot of personal data on individuals that had not actively participated in sharing this data and we offered this data more or less publicly. Although we had the best intentions (to create a user friendly service enabling people to buy local home grown food), this data could be used in ways that could be harmful for the people involved. We had unintentionally violated these people’s privacy only because they sold some home grown groceries while the consequences could have been quite unpleasant.

This situation made me think about my profession. Apparently making devices and apps very user-friendly could also cause privacy risks for its users. Sound interaction design is not necessarily sound design for privacy.

Obviously this made me rethink this concept. Even more, it made me rethink the very core of my profession. As a User Experience (UX) designer, I had grown accustomed to the idea that if a digital product was easy and fun to use, people were more willing to give it a try and that would eventually determine whether a product was successful or not. I did not know any better than to design digital (or smart) services and artefacts in such a way, that there was as little friction as possible in the use of and interaction with that service or artefact.

While doing more research on this matter, I came across a dilemma.

Smart, network connected artefacts, such as smartphones and smart watches, and smart networked services like Facebook, Google and Twitter, record, aggregate and store enormous amounts of data. Personal data connected to real humans, data – often up to a quite intimate level – of you and me. We do not seem to notice, and even if we do, we do not seem to mind. When using Whatsapp for instance, we gladly surrender our addressbook to Facebook. (Whatsapp is owned by Facebook) It has also been established that Facebook can make a detailed personal profile on a user based upon just 10 ‘likes’, including sexual orientation, political preferences and income.1

UX designers make sure that interacting with these smart artefacts and services is so user-friendly, it does not take a lot of conscious thought: conscious thought takes time and effort, but effort and time are considered negative elements in interaction with smart artefacts. However, conscious thought is important if we want to be aware that some data we submit might harm us or even worse, harm others. Like roadside grocery vendors, for instance.

This thesis covers the dilemma of designing good, user friendly computer interfaces which at the same time can leave their users in the dark when it comes to the use and possible abuse of their personal data. There are 5 chapters.

This thesis covers the dilemma of designing sound user friendly computer interfaces which can leave their users in the dark when it comes to the use and possible abuse of their personal data. Furthermore, it proposes design strategies that enable designers to have a more informed and transparent dialogue with stakeholders and end users about the interface of smart artefacts and services, focusing on the use of personal data, to answer the all-important question:

How can we ensure interface designers have the means to create interfaces for smart artefacts and services that reflect the use of personal data in a better way and therefore become more trustworthy and transparent?

Through the analysis and validation of design research using cultural probes and participatory design, I have gained insights in how people experience their relationship with smart artefacts and why they put trust in these devices and services. Furthermore, this thesis proposes an alternative approach for designing interfaces for smart artefacts by providing means to organize a visual design dialogue between all relevant stakeholders.

In chapter 2, I will focus on the dilemma of designing user-friendly computer interfaces that focus on pleasurable experiences while these pleasant user-friendly interfaces in turn pose risks to their users. Moreover, I will illustrate that these pleasurable experiences are also used to make people do things they would normally not do when given enough time to reflect on it.

In chapter 3, I will first show how humans experience their relationship with smart, internet connected artefacts and services. I will focus on how they come to trust these artefacts and services; even when they are aware of the possible risks they run. Second, using the book “Trust on the Line” by Esther Keymolen, I will explain where the trust we put in smart artefacts and services originates.

In chapter 4, based upon the findings in the research, I will propose an approach for designing interfaces for smart services and artefacts, aimed at creating more clarity and more insight in the process of acquiring, storing, aggregating and sharing personal data.

Finally, I will draw final conclusions on my findings in chapter 5.

For this project, there are many people to thank. Probably I’m forgetting names, so you know who you are. Thanks. A lot.

I would like to thank all the people that have actively and passively participated and contributed to this research and thesis. Deanna Herst, Harma Staal and Hanneke Briër, thank your for your insights, knowledge, encouragement and patience. Gerard-Jan, Ruben, Rob, Rinze, Henk, Zsa Zsa, Michiel and Mirjam, thank you for the inspiration, the conversations, the fun and encouragement. The class of ’15 felt like a close-knit group of friends.

I would like to thank Esther Keymolen for her valuable insights and feedback on the subject of trust, Jaap-Henk Hoepman for sharing his knowledge and inviting me into the world of Data Privacy and Koert van Mensvoort for sharing his inspiring projects and knowledge on speculative design. Harold Linker, thank you for kickstarting my design research with your workshop on conversational pieces. My colleagues Raymond van Dongelen, Gerben Wiersma and Derek Kuipers: thank you for your feedback and all the great discussions we had on the subject.

For all participants and experts involved in the probe research and design prototypes, the validations and discussions on the subject: many, many thanks.

Maarten, you were able to set me up with this site, even during impossible times of day. Hero.

Meriam, your patience and understanding, your love, encouragement and tenacity got me through this. I love you.